Chapter 14.

Rom-Com Sketch

Rom-Com Sketch

Analysis, interval inventory

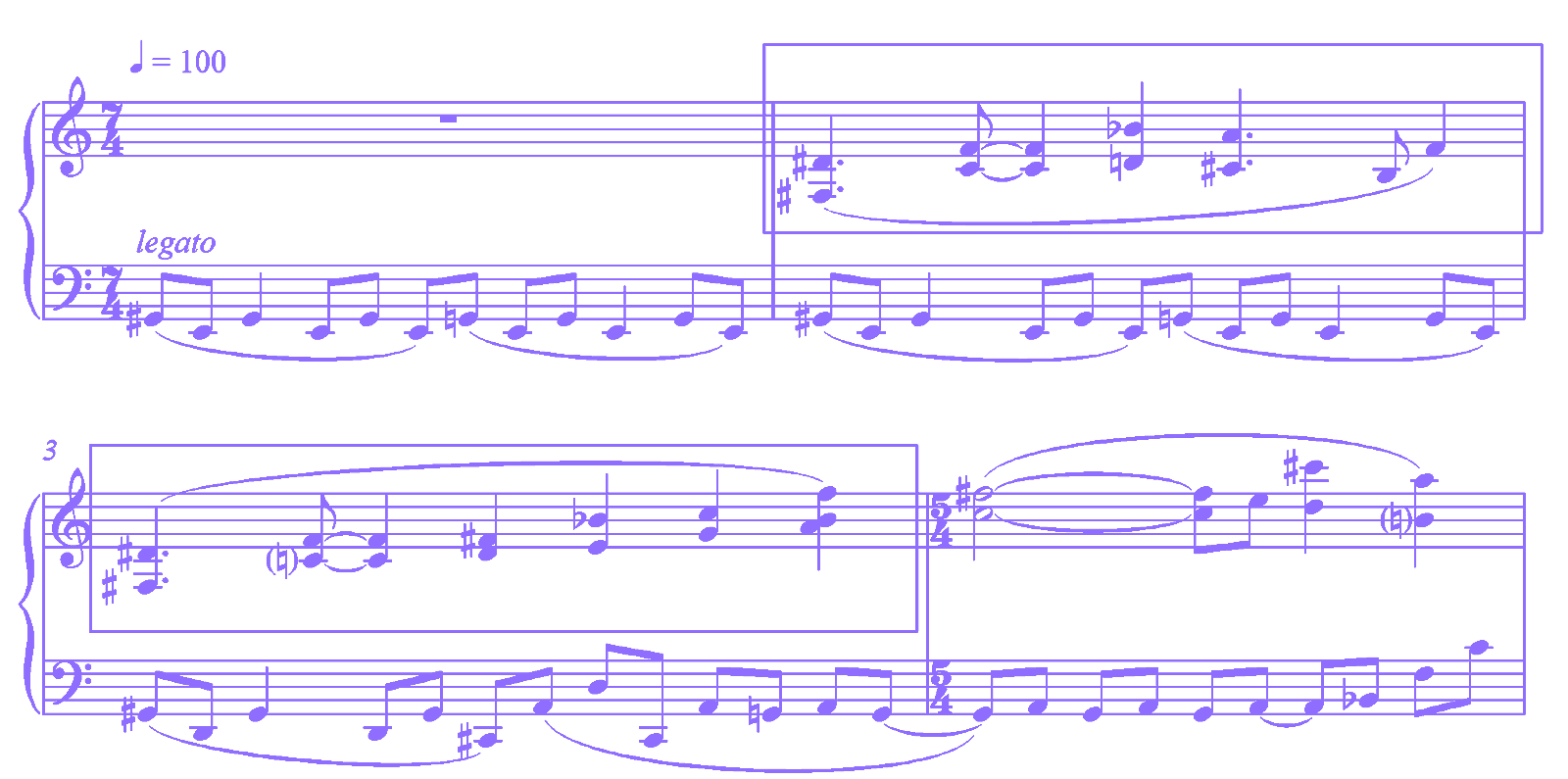

The second more extended piece we will look at is a sketch titled Rom-com Sketch. This piece also uses the Green Thumb Row introduced earlier. In this short piece I aimed to:

Exemplify all possible harmonic/melodic intervals within an octave

Utilise the tone-row in a more strict fashion

Allow the music to dictate what happens

Emphasise consonant intervals wherever possible

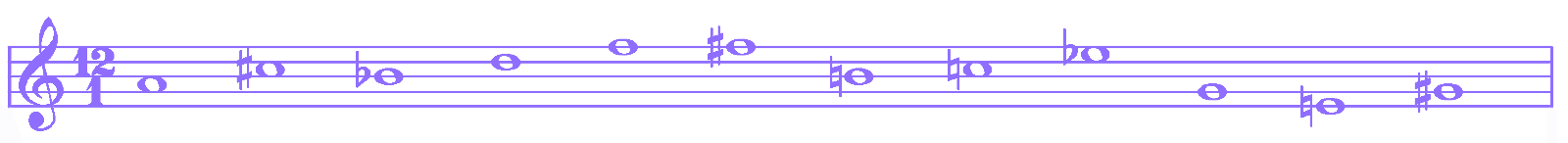

For ease of reference I have re-written our tone-row here:

‘Green Thumb Row’

A C# Bb D F F# B C D# G E G#

Rom-Com Sketch

Interval Inventory

For our purposes here, I won’t be listing the repetition of intervals. We are trying to see how much music is written compared to the abundance (or lack thereof) of intervallic content. Another way to explain this is that we are trying to see how much music is written before all of the intervals (melodic or harmonic) are covered.

Bar 1 - M3, m3

Bar 2 - M6, P4, m6,TT

Bar 3 - M2, m2, P5

Bar 4 - M7, m7

Bar 2 - M6, P4, m6,TT

Bar 3 - M2, m2, P5

Bar 4 - M7, m7

The exposition of all of the intervals (sans unison) and the presence of all of the tone-row pitches in this short time span lends itself to very effectively avoid any diatonicisation, however the presence of the low E in bars 1 and 2, and the G and A in bars 3 and 4 also effectively contradicts one of the main principles of serialism, that of not allowing any one pitch to take precedence over another.

This puts forth an interesting contrast which can be used greatly to compositional value. If we make a super generalisation regarding dissonance and consonance treatment we could say:

︎ When directly using the tone-row for composition, emphasise consonant intervals. Obviously dissonant intervals will be used, but their overabundance can easily make a passage tedious, and the strength of the dissonant intervals is lost.

︎ When working outside of the row (ie. in a tonalised passage or embellishing 12-tone material in a ‘tonal’ or chordal way, emphasise dissonant intervals.

It needs to be mentioned that the effect of putting a contradictory tone in an otherwise diatonic passage certainly has a different effect compared to putting a contradictory tone into a 12-tone passage. When a contradictory tone appears in a diatonic passage the effect is, at least to some degree, a disturbance. When a contradictory tone appears in a 12-tone passage it has to be placed very carefully to be effective, otherwise it will simply meld into its chromatic surroundings. In this way we can also experiment with adding more than just a contradictory tone, but actually an entirely contradictory passage or chord set. This can come in the form of writing tonal chord movements into a 12-tone passage, or cadential figures, or melodic lines that follow tonal parlance.

Getting back to our examination of Rom-Com, I’d like to point out how from the opening until bar 16 we avoid any feeling of tonicisation. Then from 16 to 19 an A major tonality prevails. It is introduced gradually by keeping F natural around in bar 16, and then including D# on 18 and 19. These kinds of disruptors are less harsh in the key of A major than other pitches (Bb, C, G) because they can be linked to closely related keys.

︎ When directly using the tone-row for composition, emphasise consonant intervals. Obviously dissonant intervals will be used, but their overabundance can easily make a passage tedious, and the strength of the dissonant intervals is lost.

︎ When working outside of the row (ie. in a tonalised passage or embellishing 12-tone material in a ‘tonal’ or chordal way, emphasise dissonant intervals.

︎ When working outside of the row (ie. in a tonalised passage or embellishing 12-tone material in a ‘tonal’ or chordal way, emphasise dissonant intervals.

This passage shows an example of how we can insert these contradictory tones in such a way so as to gently disrupt the A major context, but still not sound like part of the A major harmonic structure. In other words, the D# that appears, is purposefully not ‘resolved’ to E, like a leading tone to the dominant, as would be common in a more traditional setting. Likewise, the F natural doesn’t lead to F# which might imply a kind of F# minor tonality.

This brings us to measures 19 and 20 where we see material similar to the opening bars. The major difference here being that consonant intervals are emphasised and all vertical harmonies can be explained in a tonal fashion rather easily.

![]()

Note the implicated harmonies written above the staff.

Even though these chords are present on paper we don’t really hear them as such. They seem almost coincidentally chordal and are a succession rather than a proper progression.

From here we reach a short transitional passage and the start of our multiple choice endings.

An important aspect to using TONL as a compositional method is realising how you can follow the music in so many different directions. To illustrate TONL flexibility I have composed 4 potential ‘tails’ to Rom-Com, each one follows the music to a different place harmonically, and gives varying levels of resolution and/or forward motion. The characters present in these possible ‘tails’ are also of a contrasting variety.

Ending 1

Following the presentation of a consonant incomplete 7th chord (A# min 7) in measure 23, this option takes a path of least resistance and follows a consonant melodic line, diatonic in the key of C# minor. The resolution on C# makes it feel slightly close-ended as it is approached from a dominant G#. This resolution is a very complete resolution, in that the music feels like it has come to rest fully on this C#. The other sustained notes F# and G# don’t seem to need resolution of their own and can easily just continue in complacent harmony with the C#.

![]()

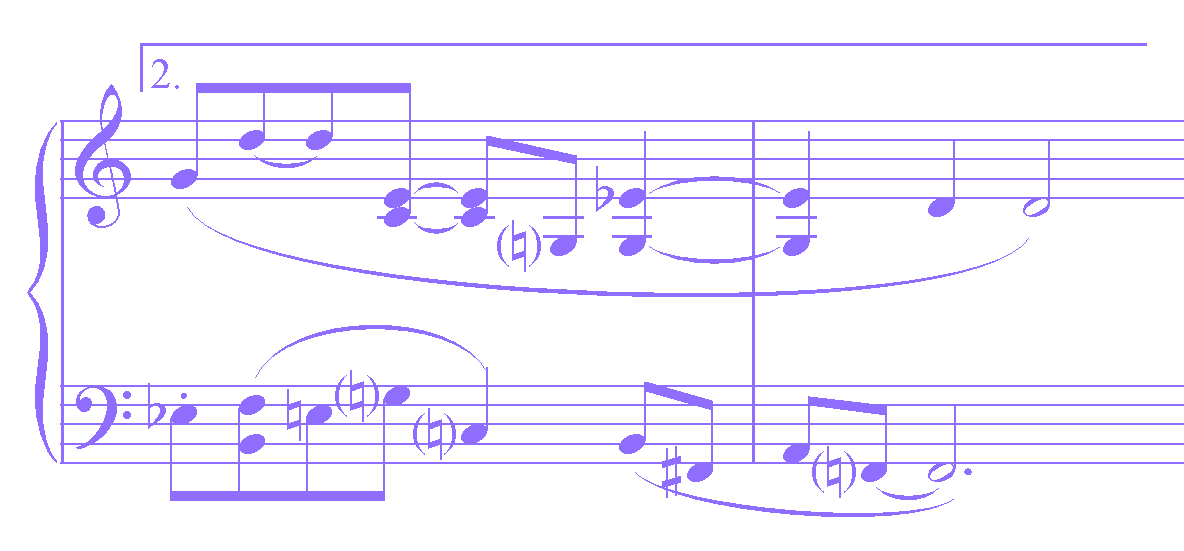

Ending 2

With ending 2 we keep nearly the exact same rhythm as the first ending, but here I revert back to following the tone-row and fill out the notes that are missing from measures 23 and 24. This creates a different kind of resolution, one that comes to rest melodically on D natural. The contour from measure 24 to 28’s resolution seems to be like an interruption of the descending melodic pattern originally introduced in ms. 21 and 22. This ending also brings us to a resting consonant harmony, but it has more potential mobility than ending 1 because the cadential figure is less pronounced, less final.

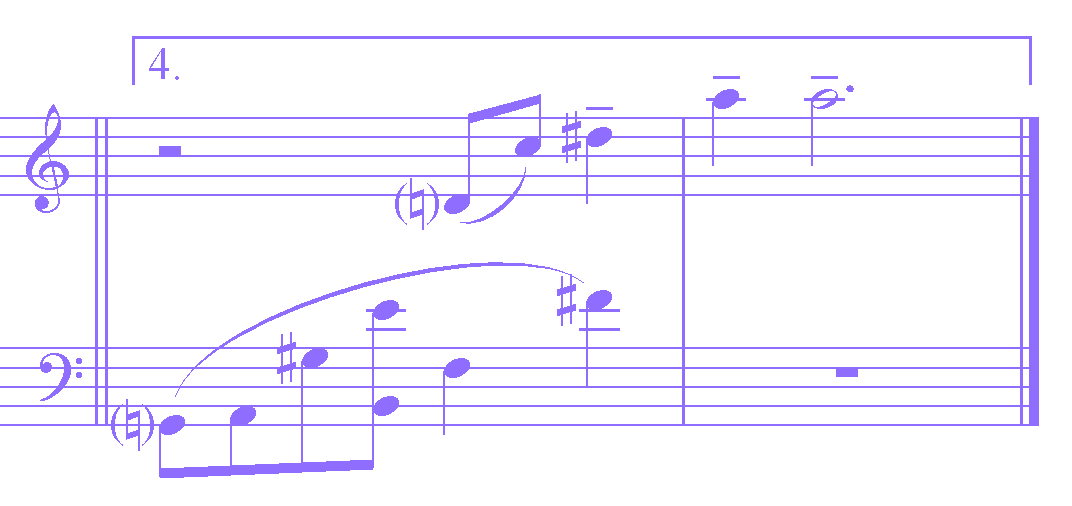

![]()

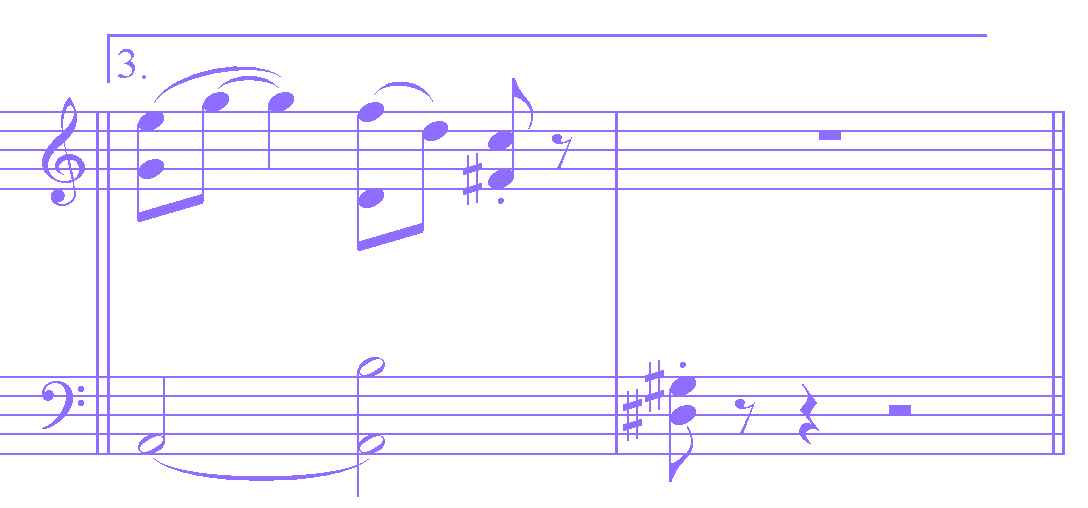

Ending 3

Tropes also often can play a wonderful role in TONL’s grammar. For ending 3, I utilise a cheeky cadential figure to bring us a brief (non) resolution on C. This example shows how we can use a tonal gesture while altering the harmony that roots it so strongly in traditionalism. These cadential figures offer endless possibilities to experiment with, but we must be careful to use them sparingly.

![]()

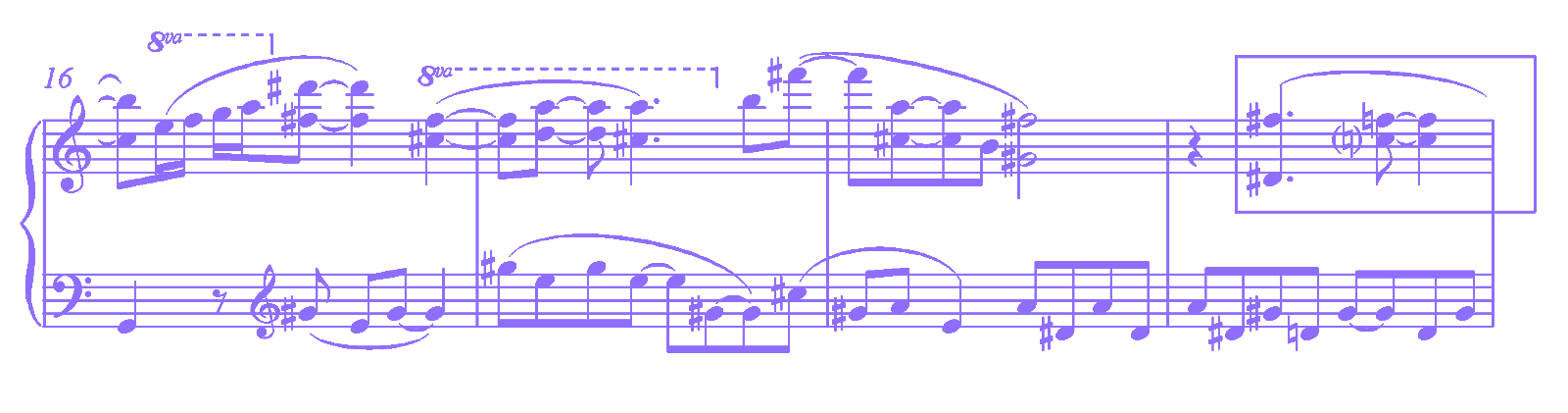

Ending 4

In the final example we can hear and see how the melodic gesture takes us away from the previously established tonal centres (D# in the treble clef, and the A# minor 7 chord in the bass clef). In this particular ending the gestural shape, and contour of the line holds precedence over the actual pitches present. The high A certainly seems highlighted as a movement away from the D# of measure 24. This ending also feels the least resolved. If the other endings represented varying forms of sentence full stops, ending 4 could be thought of more like a question mark.