Chapter 2.

Background

How the TONL method came to be

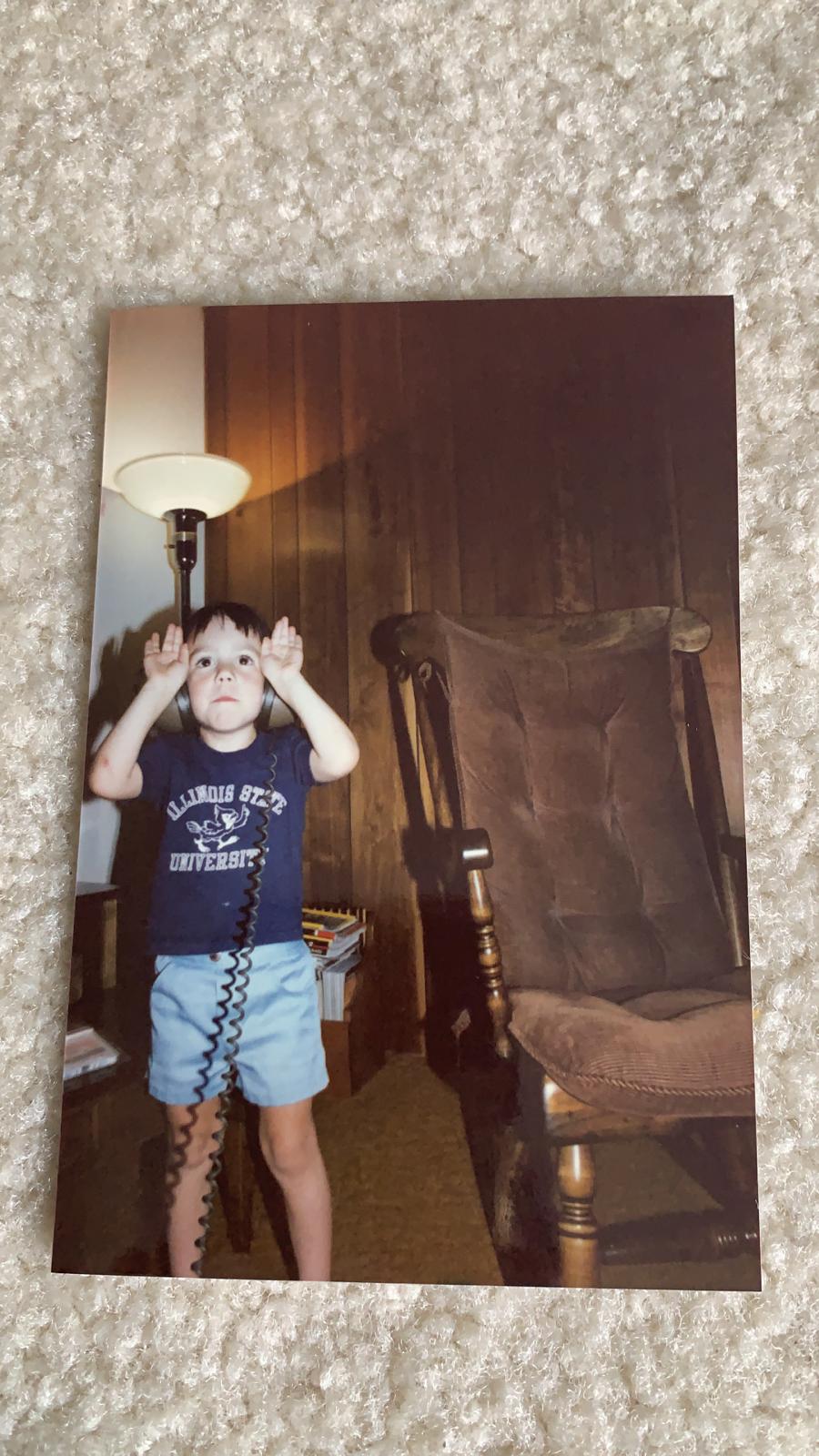

Serialism has occupied a corner of my mind ever since hearing Glenn Gould’s 1968 recording of Schoenberg’s Five Pieces For Piano Op. 23. I was about 5 years old, my mother was cooking dinner in the kitchen, and my dad and I were listening to some records he had recently purchased at our local Dog Ear Record Store. Among the collection were Guru Guru’s UFO, Stockhausen’s Gruppen, and this Schoenberg recording of solo piano music. I remember the huge, heavy, brown headphones that my dad put on my head and how he cued up the second track on the A-side. That opening movement’s music seemed to come from another planet. The way it unfolded and exposed these musical ideas turned something on in my head. Until that point, music just sort of passed me by. I didn’t really take notice of sounds.

![]()

Apart from this, I can remember consistently getting a part of a song stuck in my head, and then my brain would hold on to this little excerpt, turn it around and play with it like a musical version of a spatial awareness test. I would experiment mentally with moving the musical tidbit around rhythmically, imparting different accents to it, and generally just messing it up, until eventually I couldn’t remember where I had even started. All of this happened before I had any idea how to write or read musical notation, or had begun playing an instrument.

The music that I was introduced to on this Glenn Gould record led to other early serial works such as Webern’s String Trio Op. 20, and String Quartet Op. 28, and the music of Milton Babbitt. Admittedly this kind of music has become an obsession of mine more than once.

It wasn’t until around age 15 that I had a composition teacher who encouraged me to explore composing using this serial method. Coming from a background of jazz and improvisation, the strict rules of serialism were hard to get used to at first. I liked the idea of putting limitations on certain compositional material while keeping the freedom in other aspects, and had done just that in many other musical settings but never in the same way that serialism imposes on the music. We didn’t just serialise pitch sequences, but rhythm, dynamics, and articulation as well. Our class had a rather peculiar core of musicians (piano, guitar, trumpet, saxophone, violin, clarinet) in it that we could write for and so I set about writing my first compositions exploring the possibilities of this new method.

At this point in my life I hadn’t yet begun to play cello. I had no experience of being in the ‘classical’ music world and had no classical music training (whatever this is meant to mean). It was my first encounter with musicians who didn’t come from a background of creating music themselves, but rather a background where they were trying to accurately translate the notes on a page into sounds. When we would rehearse I would refer to harmonic sequences and chords in a piece that seemed very obviously to be structural markers, but these students didn’t hear the music in the same way. For them, (and as I have discovered over the years, many musicians) music theory is a separate entity of music, something that one could easily ignore and because they put their fingers in the right places, the right sounds come out of the instruments.

At this time I also discovered that my musical upbringing which consisted of Schoenberg, Monk, Sun Ra, Varese, Zappa, Takemitsu, Metallica, Slayer, was not the norm. I had heard Mozart, Beethoven, and Bach but I didn’t share the reverence for them that my classmates did. For me music was and is about creating something new. At that young age what I heard when I listened to these classical masters was antique, ancient. It wasn’t until I developed a love for history that I went back and took a closer look at their music. A subconscious decision that brought about its own set of musical obsessions.

I also quickly discovered that not only my classmates, but also some of my music teachers really hated serial music and the composers who wrote this music, so I suppressed my need to write in this way and followed the other student’s leads. It was much easier to get performances, and audiences seemed to like my music more. It is from these beginnings that my foundation and approach to writing music took shape.

No matter how much I tried to repress the desire to write this way, the desire just kept getting stronger. I had to find sneaky ways to incorporate these sounds into my compositions and little by little this combination of traditional harmony and serial music became part of my musical vocabulary.

For me, music written using serial grammar takes on an entirely different kind of enjoyment when you play it. The first extended tonality piece that I can recall playing is Pierrot Lunaire. While this isn’t serial music, it was my first free-atonal experience as a performing instrumentalist. I had the incredible opportunity to play Pierrot during my undergraduate studies at Illinois State University under the direction of Glenn Block. When other schools and venues heard that we were performing Pierrot, they also programmed the piece, and since I had already been performing the piece for a few months I was the go-to ‘Pierrot’ cellist for hire. This carried on for about 6 months and culminated with a series of concerts held at Eastern Illinois University directed by Peter Hestermann. The concept of his concerts was to pair music of the early 1900’s with horror films of the same time period. Hestermann’s idea was that these movies would have been so much better served had they used music of these early avant-garde composers instead of the boring, pedestrian stock music that was used on the original soundtracks.

Upon entering university I was met with an onslaught of different musical viewpoints. The major trends in academia at that time were minimalism and the music of the New Complexity. There was also a huge contingency of composers who embraced the abstract graphic notations of Earle Brown and John Cage. While these kinds of music interested me very intensely for varying periods of time nothing seemed to have the staying power that the early serialists held in my mind. But alas, serialism found its way into antiquity as well. Berg’s Lyric Suite is nearly 100 years old; the freshness that his harmonies once brought to the world are now looked at as things to be studied in a classroom, rarely heard in concert.