WHY YOU SHOULD LEARN THIS PIECE

Beckoning by Serra Hwang

When I first saw a performance of Serra Hwang’s Beckoning nearly 20 years ago, I was pursuing my bachelor’s degree in cello performance at Illinois State University. The new music trends that permeated the music department at that time ran thick with the music of Steve Reich, John Cage, and David Maslanka. Music of Asia was really relegated to a few select courses of ethnomusicology and the occasional programming of Tan Dun, Hiromori Hayashi’s flute music, and Toru Takemitsu’s percussion ensemble music. You can imagine my surprise hearing Beckoning for the first time in a concert hall with my teacher as the soloist. This piece has stuck in my mind ever since as being not only a great addition to the repertoire but also a great link between Eastern and Western music that isn't contrived or forced.

Serra Hwang was a teacher at Illinois State University at this time and she was doing something altogether different. Her music is not a mash-up of musical styles; it is not one kind of music influenced by another kind of music. Rather, Hwang’s musical voice is something genuinely unique and self-made. Beckoning doesn’t sound like a composer borrowing instruments from one musical heritage and trying to make them work in a new context. Instead, Beckoning creates a sound world unto itself, one of fresh sounds and curious synergy.

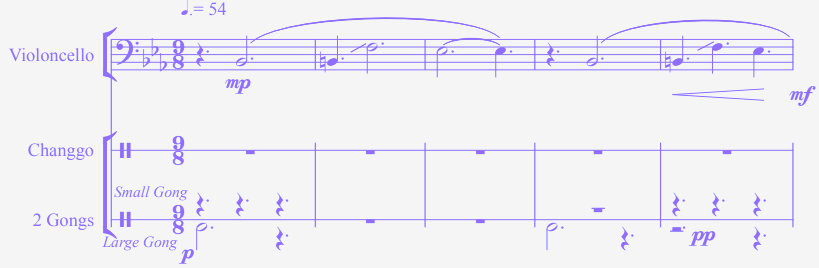

Upon first examination of Beckoning, you will notice that this piece is written for 3 players. A solo cellist plays the melodic material while two percussionists play gong and changgo, a two-sided hourglass shaped drum. These parts are very interconnected, and the piece would lose a great deal of its power, drive, and energy if Hwang were simply to have written the piece for solo cello. If we take a look at the opening few bars, we can see how the piece opens with a calm contemplative beginning. The percussion instruments start very sparsely and gradually become more regular in rhythm by bar 15.

One of the coolest aspects of the piece is that the music all sounds very organic and spontaneous, even though it is entirely notated and there is no improvisation. Part of this comes from the gong and changgo parts. Instead of playing a constant and easily trackable repeating rhythm, they play an ostinato figure that spans 4 bars and intersperses groupings of 2 and 3 creating a kind of unsettled underlying pulse. This results in a very fluid feel of metre and allows the melody to sing freely over it. These melodies are beautifully lyrical and expressive - a testament to why we play cello.

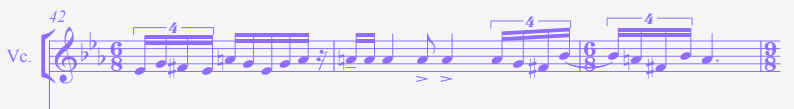

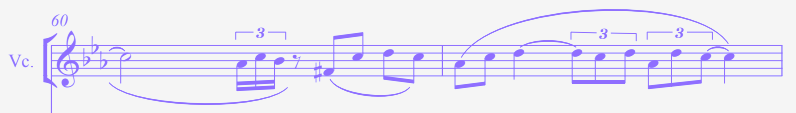

Another element that contributes to this organic feeling is the cello line’s improvisatory nature. The melody starts by sticking quite closely to the compound metre triplet feel, but as it develops it becomes more urgent. Hwang starts to include tuplets that contradict the underlying rhythmic structures and writes phrases that deny the confines of the barlines. This is something that happens quite frequently in improvised music.