Short Series and Long Series

Composing using a serialised method with a tone row that doesn’t use all of the 12 pitches is nothing new or ground breaking. A few great examples of this can be heard in Ruth Crawford Seeger’s Diaphonic Suite No. 1 and her String Quartet 1931. Stravinsky’s Septet also gives us an insight into how we can work with the serial method while using fewer than 12 tones. So how would this work in tandem with TONL? We can approach this the same way that we did the rows of 12 pitches, but we need to be aware that with fewer pitches present it becomes much easier to get magnetically drawn to a key. This being said, it is all the more important to create a row that has few or if possible zero resemblance to a traditionally tonal construct.

For example:

D F C# D# G A G#

The potential for interesting material derived from the set above is plentiful. Also, when we move into more diatonically based material it will contrast nicely and rather easily create different characters between the two.

If we take the viewpoint from the opposite extreme, we can create a tone row whereby all of the pitches when considered in their gestalt would make up a defined key.

For example a potential 7 note row could be:

B F# G# D C# A E

Although the row doesn’t leave us with much in the way of sounding like anything other than A major and its modal counterparts it does let us take a different perspective on TONL’s overall approach. Where previously we started with a 12-tone row and found different ways to move away from it towards varying tonal centres, here we can find ways to move toward a more chromatic vocabulary. By introducing contradictory tones and avoiding tonicising gestures interesting results can still be achieved.

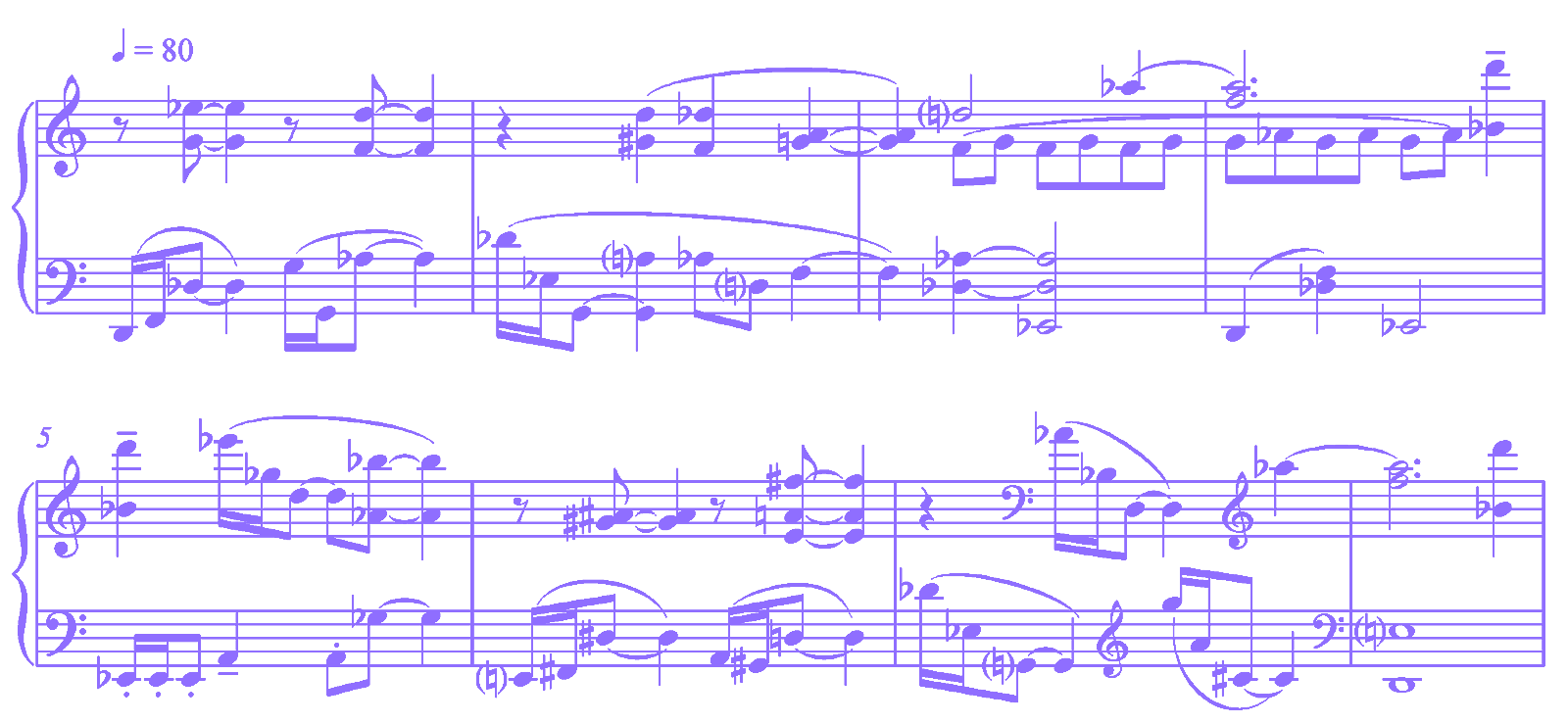

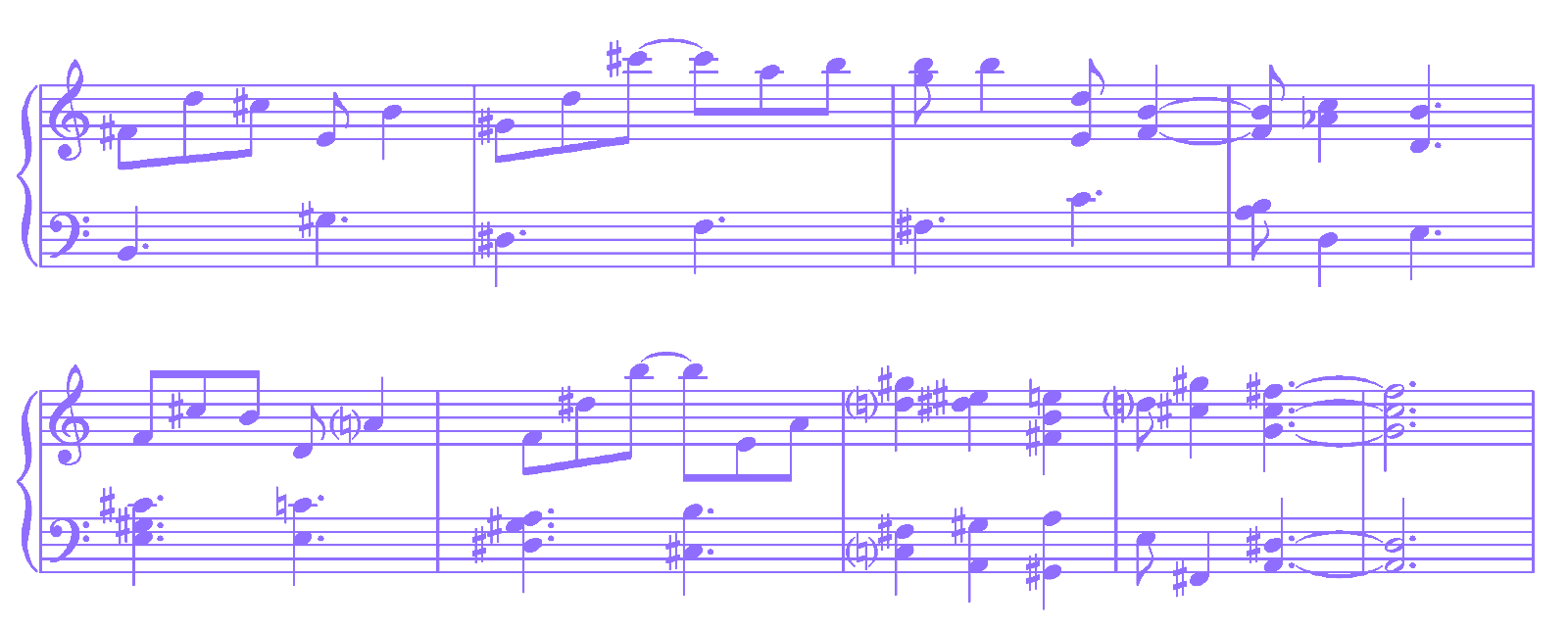

The above passage sounds rather like a pandiatonic composition similar to material that one might encounter in the music of Milhaud, or Copland.

In the next step I took my original row of 7 notes (which were purposely selected to fit within the key of A major) and introduced 2 more pitches (C natural and G natural). The passage below demonstrates this method, which really still sounds rather tonal to the ear. I tried to maintain the contour and texture of the original piece while intuitively changing certain notes to accommodate for our two new pitches added to our row. We should notice that I didn’t re-write the row to include C and G, but rather kept my original row, and simply altered the previously composed material. The results would be quite different if I ‘inserted’ the new pitches into the original 7-tone row instead of ‘tweaking’ the pandiatonic material from above.

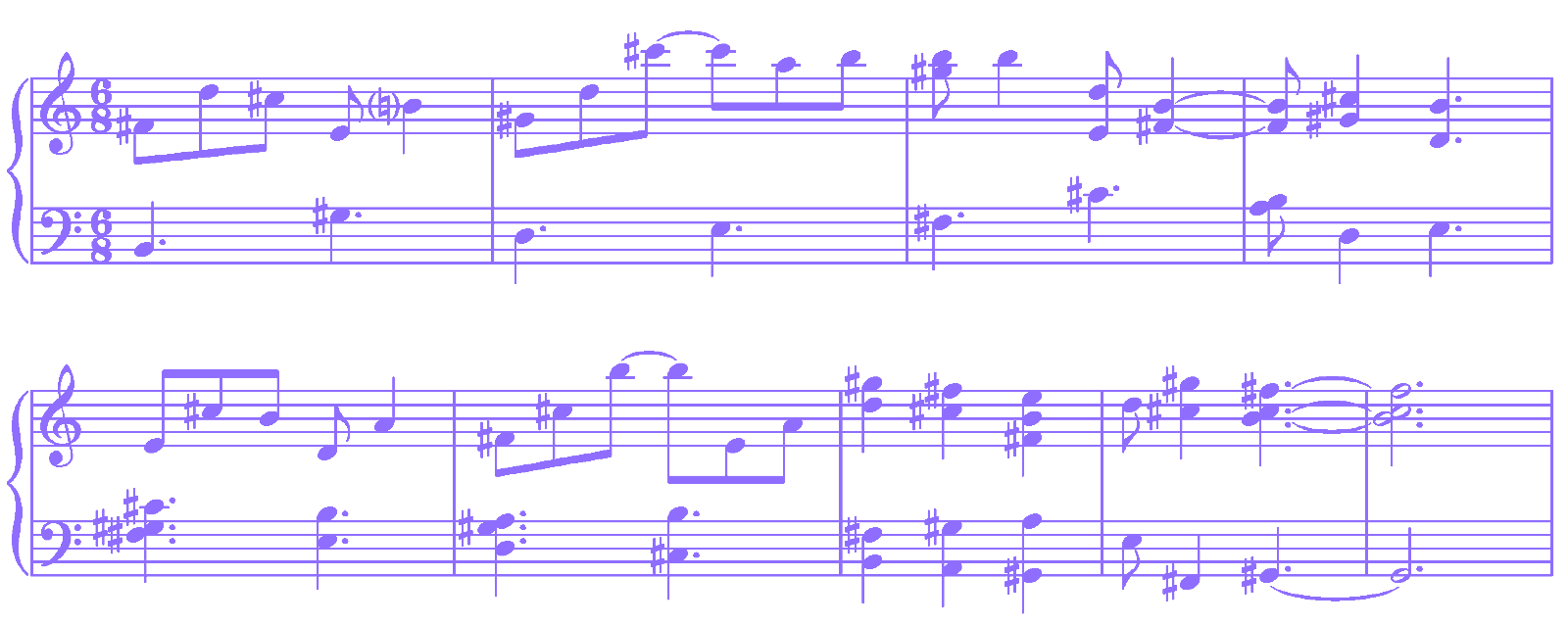

I continued again in the same fashion as the previous passage this time adding two more notes (F natural and D#). The same intuitive approach was followed and the result is now a passage of material that teeters on the edge of aurally identifiable key centres. We could examine this passage as we have previous ones and discover how these small additions and alterations to the pitches affect the impetus of the music, but really the most important thing to note is how the music sounds. As we gradually add these chromatic pitches to what would be A major, the strength of the diatonic interval relationships weaken, and the pitches begin to take on an importance of their own. This is largely what TONL helps to explore. TONL is at once a systematisation of pitches while also being a method by which we can move away from this systematic organisation and discover new ways of approaching harmony, melody, and composition in general.

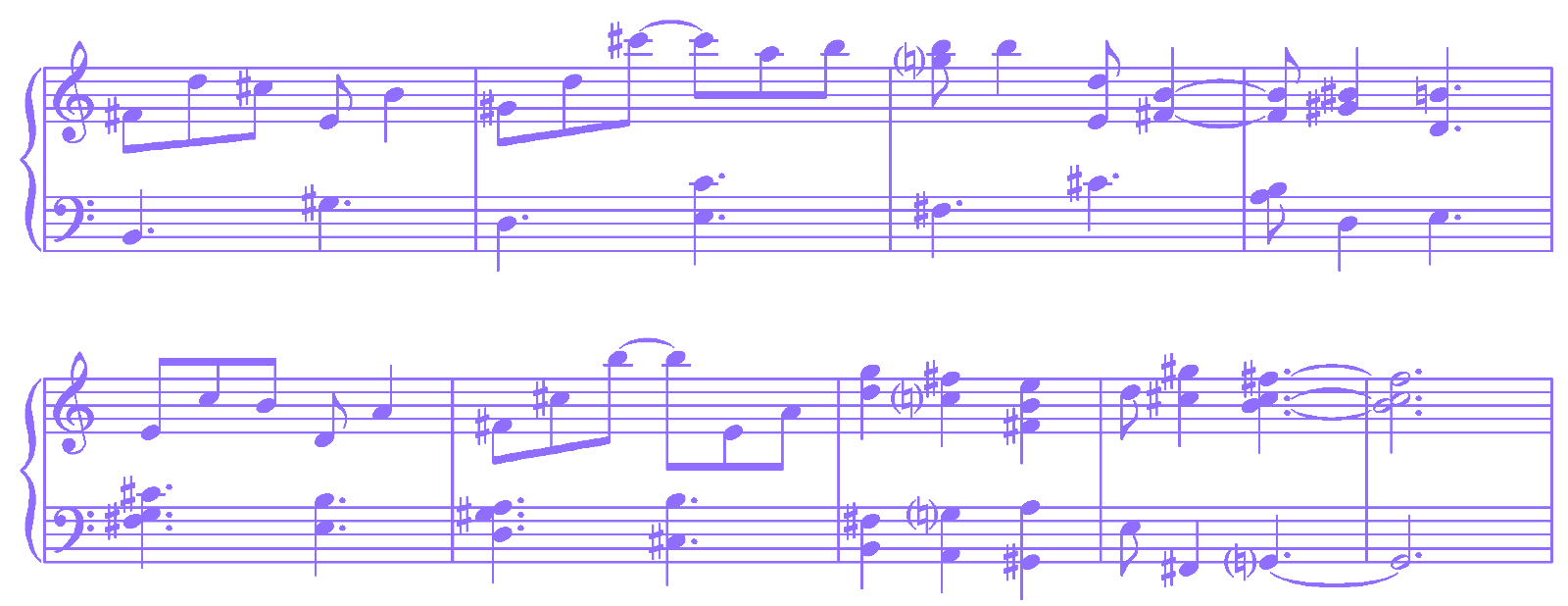

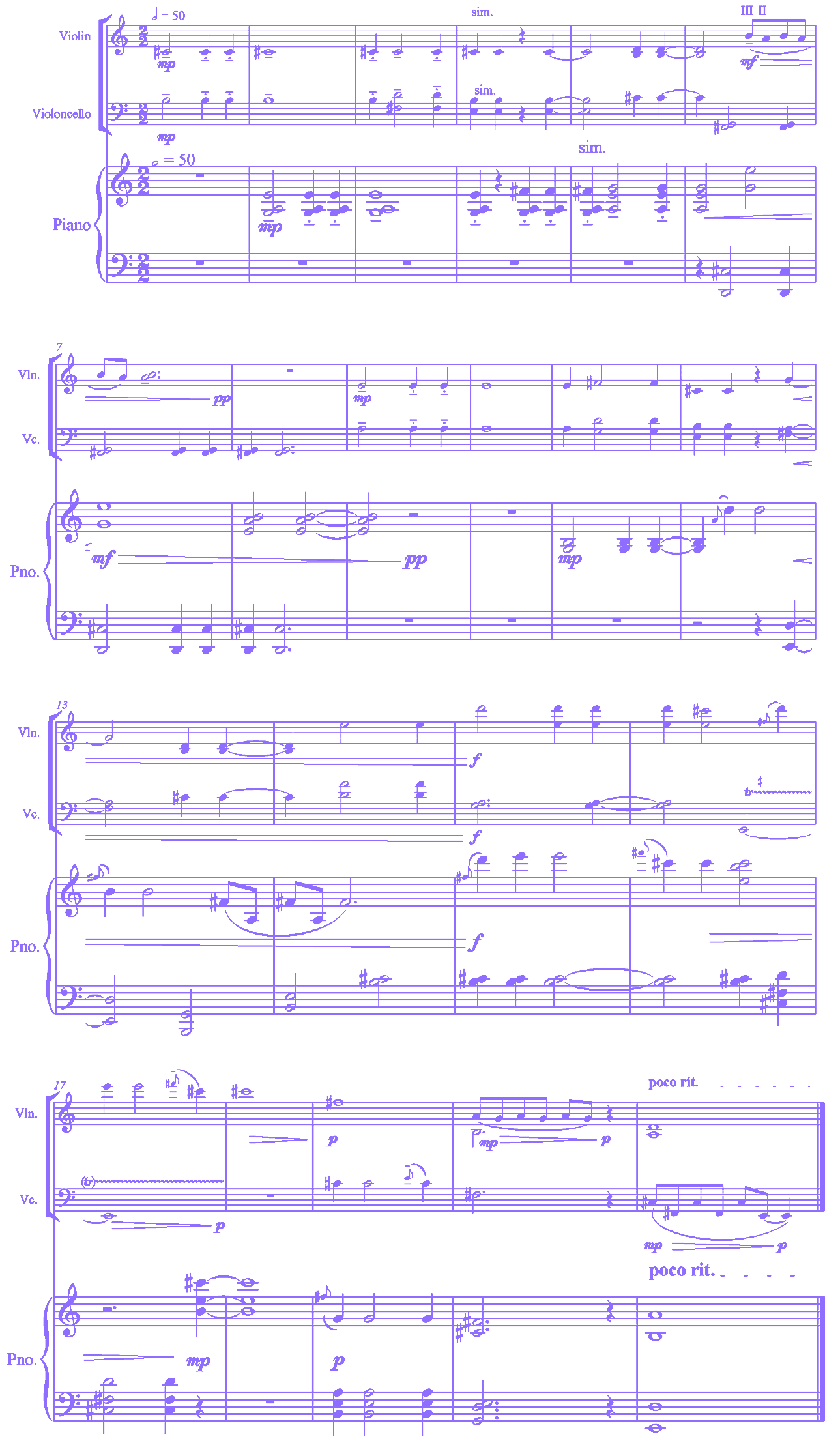

I composed another example that does something similar to the above method with one added caveat. This piece strictly follows the serialisation of the following tone-row:

C# B E A G F# D

Obviously this row fits into D major or B minor. Extra care has to be taken so that we don’t inadvertently begin to sound like either of these keys. With a bit of practise, you’ll be able to avoid the magnetism that the corresponding major and minor keys possess.

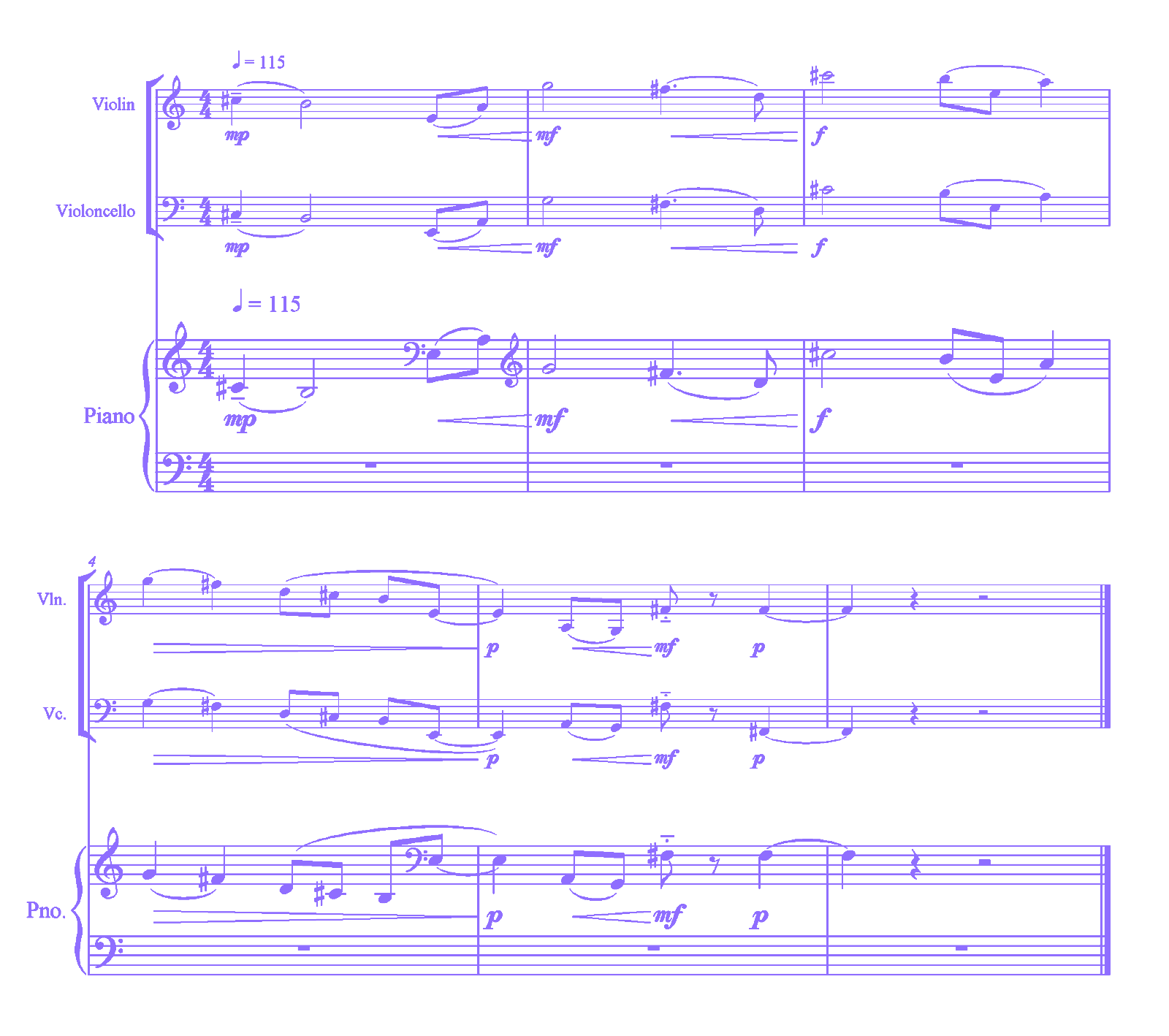

The excerpt below shows another example utilising this same method, this time written for piano trio.

EXCERPT 2