Chapter 8.

What is TONL?

Examples, bi-directional row usage, tonal implications

TONL is a new way to approach the 12-tone method. It is difficult to deny the universality that this method imposes, and by using the phrase 12-tone method in its title it at once becomes a misnomer. TONL may have its roots in the 12-tone method, but certainly contains equal influence of bi-tonal composition, traditional tonal composition, counterpoint, jazz harmony, cyclical javanese gamelan structuring, and many others. To explain the influence of all of these upon TONL is beyond the scope of this book, but I will point out some of the inspired facets where appropriate. TONL is not meant to be a method of analysis. It presents different ways to write music using a tone row as a starting point. More specifically, as will be seen in the section Composing with TONL, TONL is a direct way to translate emotion into music.

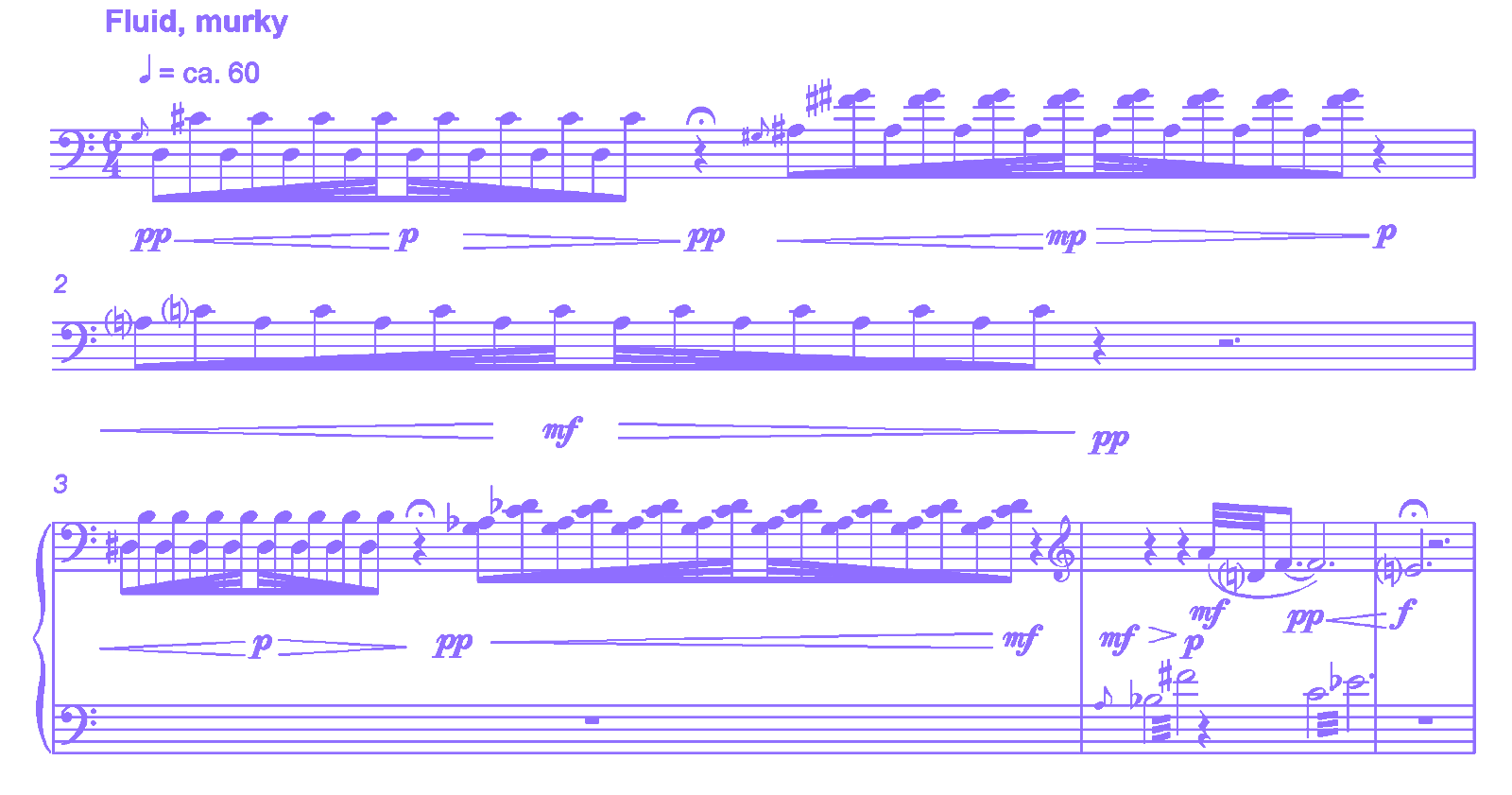

To give the reader a very brief idea of how using this method is different from traditional serialism we can take a cursory look at the example below.

(using green thumb row)

![]()

We will notice there appears to be no relation to serial music. The pitches don’t follow the tone row’s order, however pitches are represented almost totally equally. All pitches occur 3 times with the exception of F natural which is ever so slightly over represented with 5 occurrences, and F# which only has 2 occurrences.

A cursory examination of Trying to Save a Burning Picnic bars 1-7 (below) illustrates one of the many varying ways to use TONL.

Bi-Directional Row Usage

The tone row used for this composition is:

From the beginning of the piece, clearly I am not following the strict order of the row. I chose my pitches starting on both sides of the row at the same time. Working in this way I make my way towards the middle of the tone row, and avoid using the two pitches F and E. The second half of the bar starts by using this same method of pitch selection again and carries on until the final E of bar 5. There is one element that sticks out as being different from this Bi-Directional Row Use, which is the D min melodic figure that appears in the piano Right hand bar 4. More on this later.

To better understand how this Bi-directional row usage works, we will take a more in depth look at a short excerpt below.

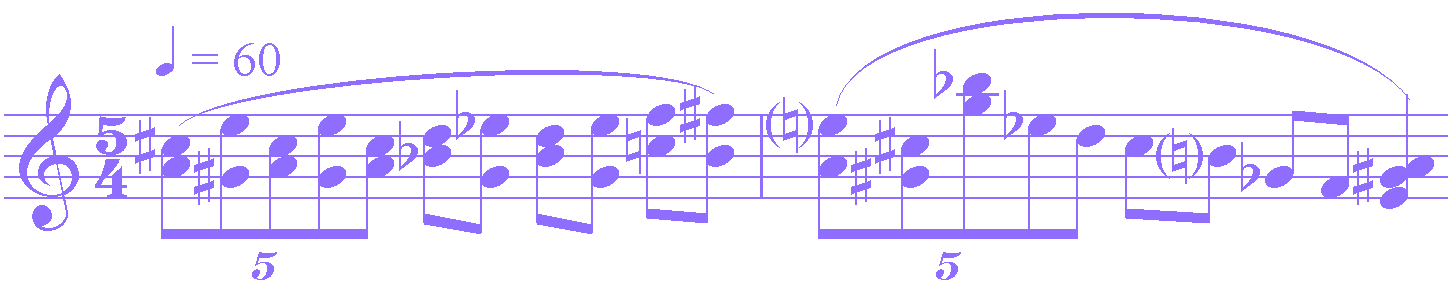

Here is a more straightforward example utilising this same method. It employs the usage of ‘Green Thumb Row.’

You can see that we make our way through the row working from both sides of the row simultaneously. We should also observe that there is a tendency towards favouring consonant intervals, and no attempt to advertently avoid a key establishment. This is something quite important to composing using TONL.

Traditional texts on the 12-tone method always emphasise trying to avoid triads, and sequential pitch figures that could imply a key. ‘...avoid more than two major or minor triads formed by a group of three consecutive tones… because the tonal implications emanating from the triad are incompatible with the principles of atonality.’ (Krenek, G. Schirmer, New York, 1940)

In TONL this rule is not a priority. In fact, the establishment of a key is sometimes encouraged.

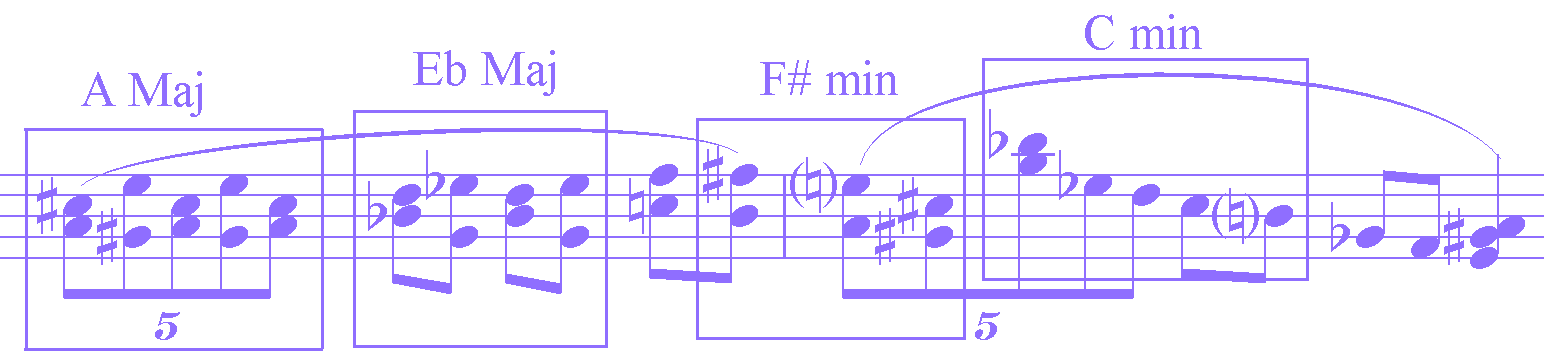

If we look at the tonal implications of this passage the following key relationships emerge. Some are more strongly represented (A Maj and Eb Maj) and some are more weakly presented (F# min and C min). By looking at this kind of analysis we can see an interesting pattern of tri-tone relationships start to come about and we could consider utilising this as linking material should we decide to develop this idea further.

It should be noted that simply by using your row in this way doesn’t implicitly mean that you will be getting more consonant intervallic choices, nor should this necessarily be the goal. This is simply one way to more easily float between traditionally tonal elements and 12-tone material while still remaining within the confines of the row. You could just as easily write this passage with the intention of emphasising dissonant intervals, and arrive at an equally powerful musical gesture.