WHY YOU SHOULD LEARN THIS PIECE

Bunraku by Toshiro Mayuzumi

For those of you who read last month’s article about Chen Yi’s piece Memory, you’ll recall that there were some parts in the piece that I mentioned sounding like the er hu. Earlier last year, I also wrote about a piece from Korean American composer Serra Hwang, titled Beckoning, where the composer wrote lines for the cello that resemble vocal lines in traditional Korean music. This cross-cultural type of composition is not unique or uncommon; it is, however, quite rare to find well written pieces that fit into this category. Bunraku is one of these pieces.

Toshiro Mayuzumi is a composer whose background and compositional style embrace both Western art music and traditional Japanese music. His piece Bunraku brings these two styles together in a wonderfully creative way. The title ‘Bunraku’ refers to Japanese puppet theatre. The accompanimental music of Bunraku is typically only a shamisen and a vocalist, and Mayuzumi does a fine job of maintaining this feature in his piece for solo cello.

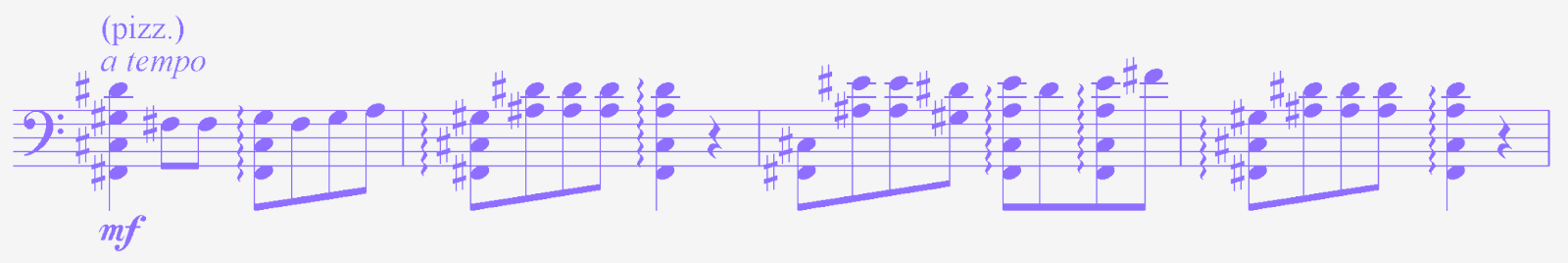

If you have heard the shamisen before, then you know it is a plucked string instrument with a tone colour similar to the banjo. Composers who write for the shamisen traditionally make abundant use of octaves and half steps, evoking something similar to the western Phyrgian and Locrian scales. The music of the theatre includes long improvised sections as well as more structured songs. In Bunraku’s opening lines we are effectively playing the music for opening the curtain at the theatre.

This section is followed by a recitativo section that introduces the ‘singer’s’ voice, played arco by the cello while continuing the accompanimental pizzicato. In traditional shamisen music, the score is notated using tablature, a notational method quite common for guitar, bass, and banjo. The major advantage of using this method is that the player is told exactly where to place their fingers on the fingerboard. This is particularly helpful because these instruments play in a variety of tunings, and using traditional staff notation would be quite challenging to read and play if the location of our notes were always in different places. The disadvantage is that this notation doesn’t really have a great way to indicate rhythm, which results in a somewhat freer interpretation of rhythm.

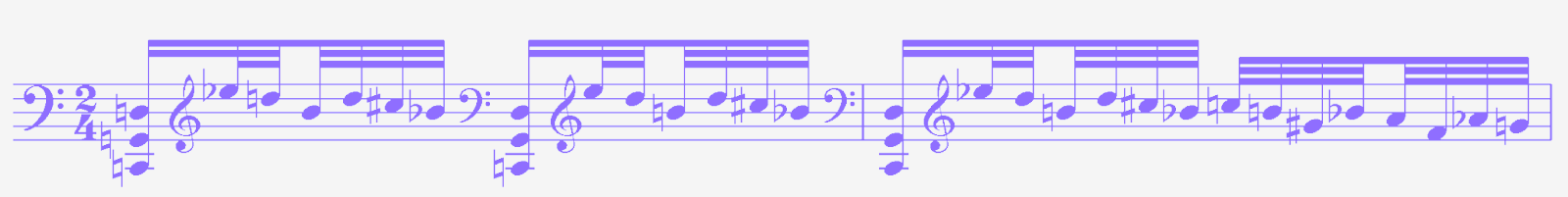

If you look at the lyrical section below, it perhaps looks rhythmically challenging at first, but really the composer is using traditional western music notation to write rhythms that would usually be left up to the performer to decide. As such, we can approach these with a lot more rhythmic freedom - they needn’t be so metronomically strict.