Chapter 10.

Contradictory Tones

Contradictory Tones

Another method that has made itself apparent in some of my compositions is the usage of tones that contradict an implied tonality. These could be roughly equated to a more modern definition of a non-harmonic or NCT (non-chord tone). In essence they serve the same purpose: to build, hold and potentially resolve tension. To give a more broad description of how this could work I pose the following: imagine a passage written diatonically in the key of D. Then imagine any NCT’s presence in this same texture. It must be prominent enough to actually contradict the prevailing harmonies, so very short rhythms, gracenotes, weak tone colours etc, don’t really effectively accomplish this idea of a contradictory tone. It takes some finesse and trial and error to decide which contradictory tones to use, and how to use them to greatest effect in a given passage.

This concept of contradictory tone also applies to music written in a serialised passage. If we establish this row’s repetition within a given part of music and then disrupt the order of the row, this too will feel like a contradictory tone. The effects of these two major categories of contradictory tones are vastly different and are discussed at length here.

‘Green Thumb Row’

A C# Bb D F F# B C D# G E G#

A C# Bb D F F# B C D# G E G#

This piece was composed to give the reader a clearer insight into how we can drift between serialised passages and tonal passages smoothly. In this section I have used contradictory tones, avoidance of triads, and employed the recurring harmonic interval of the major 9th, and minor 7th. I have provided a number of analyses to show different aspects of the music.

We will examine each section individually to better elucidate its compositional strengths and weaknesses.

In the opening 4 bars I did my best to avoid any particular tonal centre but gave slight preference to usage of the pitch A. I did this purposely so as to hint at the coming of bars 5 and 6 in which I establish something like an A major tonality.

Pitch Inventory

(S+ = Very Strong, S = Strong, N = Neutral, W = Weak, VW = Very Weak)

(S+ = Very Strong, S = Strong, N = Neutral, W = Weak, VW = Very Weak)

Pitches

A

C#

Bb

D

F

F#

B

C

D#

E

G

G#

A

C#

Bb

D

F

F#

B

C

D#

E

G

G#

Occurences

5

5

4

4

1

2

2

3

2

2

4

2

5

5

4

4

1

2

2

3

2

2

4

2

Strength

S+

S+

S

S

N

W

W

W

W

VW

N

VW

S+

S+

S

S

N

W

W

W

W

VW

N

VW

The determination of a pitch’s weakness or strength is subjective and totally up to the composer. Some things that I take into account are:

How many times does the pitch occur? (frequency)

Does the pitch occur in the passage’s extreme registers (ex. a comparatively high or low note)? (range)

Is the pitch sustained for a longer duration than surrounding notes? (duration)

Is the pitch dynamically, agogically, or timbrelly emphasised? (emphasis)

Does the pitch start or end a prominent melodic line? (placement)

Other factors could come into play, but these five should give you a starting place. You might notice in the above chart that the pitch F only occurs once in this passage, while the pitch E occurs 4 times, but they both share the representative strength of a 4. To my ear I felt that the fashion in which the pitch E is presented isn’t particularly exposed. It doesn’t attract a lot of attention, whereas the F is sustained for a fairly longer note value and acts as a sort of crux for the four measures to balance on so in this way they seemed to be about equal in importance.

I certainly don’t do this kind of analysis while I am writing. This weighing of the pitches presence or lack thereof, and how this influences the feeling of a given section happens in the back of my mind. It could be beneficial to the composer wishing to try this method to analyse their own music after completing it to see what patterns emerge, and to see how and why certain sections are more effective than others.

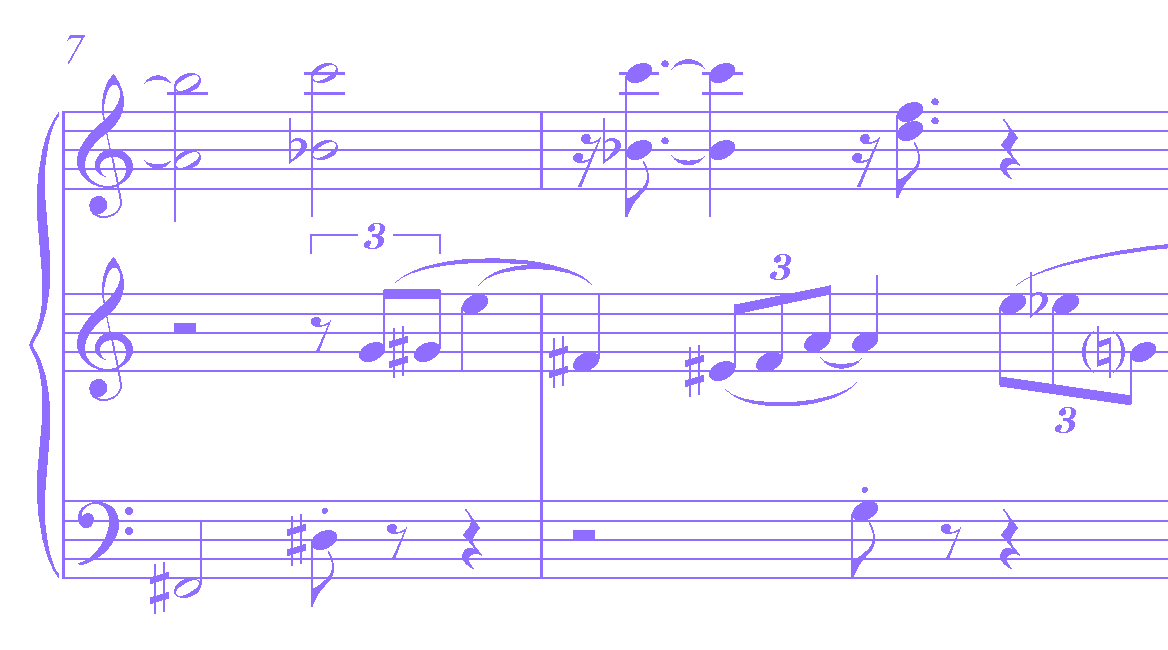

This brings us to bars 5, 6 and the first half of bar 7. These 2 and a half measures exemplify what I call a pure key. In this case the pure key of A major. All pitches would fit diatonically into A major. Pure keys need to be handled somewhat carefully lest they become too firmly rooted and quite difficult to get out of.

This isn’t always the case, sometimes we want to have a very firmly rooted pure key, but for this piece’s intent I followed two important guidelines.

Avoid the leading tone of the implied key. In this case G# is not used at all in the passage. The later half of the excerpt has F#’s in the bass which could imply F# minor but by avoiding E# (leading tone of F# minor) this passage remains quite flexible.

-

Avoid dominant tonic relationships. In this excerpt I avoided writing E moving to A, or C# moving to F#. It is not always imperative to avoid these types of resolutions. They can definitely be used quite effectively in modal settings where dominant to tonic relationships are skewed.

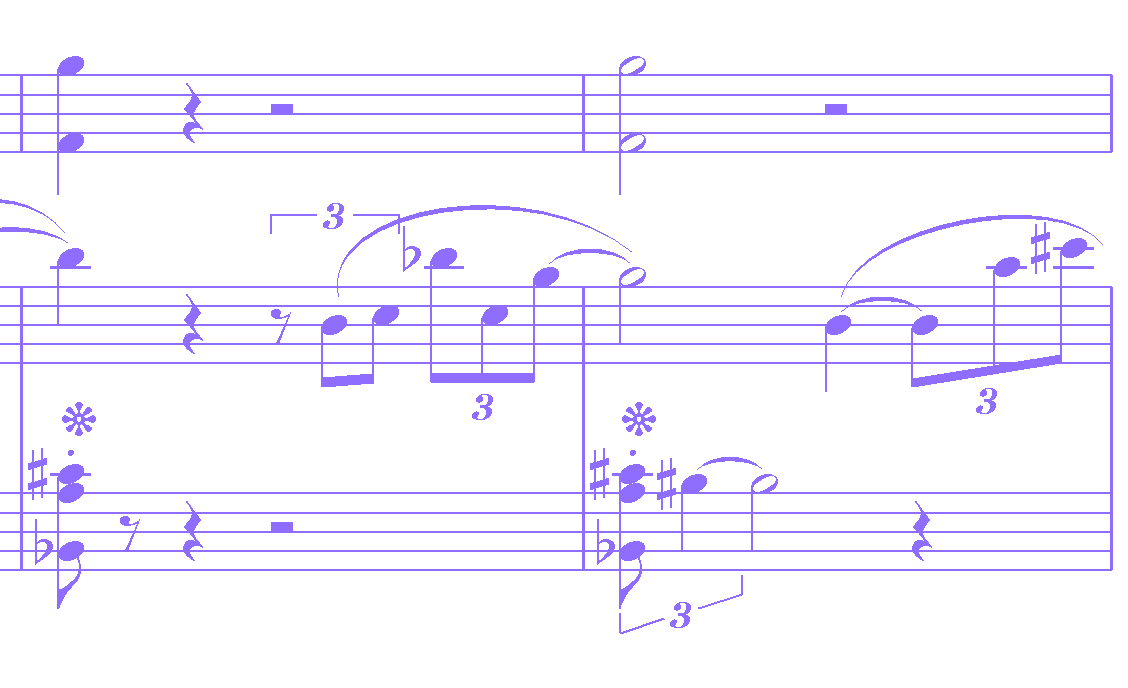

Gradual approach

Next we can take a brief look at the second half of ms. 7 and ms. 8. Rather than do a comprehensive pitch inventory again of this section I will simply point out how we have all but two pitches of our 12-tone row present in these two measures. This avoidance of C# and B here is not accidental. In essence, I have used only 10 of our pitches in this section to create a small bridge between two more tonal passages. By eliminating these two pitches that are both part of our previously established A major, it makes moving to another tonal pitch centre much smoother.

To explain this another way, we could say that we have in effect evened the playing field between our two pitch centre’s of A and Eb. Of these 10 present pitches, the tonality of Eb major has an ever so slightly stronger magnetic pull. Of the 10 used pitches we have:

Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb, C,

that all fit into Eb Major.

that all fit into Eb Major.

D is present in both keys so is effectively cancelled out, leaving

A, E, F#, G#

that fit into A major.

To simplify these findings in we can deduce:

When moving from one tonal centre to another we can increase or decrease each key’s representative pitches to better facilitate a suitable transition.

Using traditional harmonic grammar we try to find common chords, or chromatic alterations to move in and out of keys. Using TONL, we can use our tone row to accomplish this same feat.

Example 2

Below is an example of how we will use the ‘Green Thumb Row,’ to navigate us from the key of Bb Major to C# minor. This example is completely removed from any musical context, we are just looking at how this could be accomplished on paper.

Key 1

Bb Maj

Bb C D Eb F G A

Bb Maj

Bb C D Eb F G A

Key 2

C# min

C# D# E F# G# A B

C# min

C# D# E F# G# A B

Green Thumb

Tone Row

A C# Bb D F F# B C D# G E G#

Tone Row

A C# Bb D F F# B C D# G E G#

If we want to make a transition from Bb major to C# minor we can link these two with our tone row, while avoiding C and G. These two pitches which occur only in our first key will make it a rather abrupt transition if we keep them around. Furthermore, we don’t want to approach our new key with the potential of exposing a C/B# leading tone that would too strongly suggest C# minor. You might be wondering why not avoid Bb or D or Eb, or F or A. Through much trial and error in my own compositional endeavours I have come to the following conclusions:

Because Eb, and A are present in both keys (enharmonically) they are stronger if we keep them in the musical fabric. If we eliminate them it doesn’t really aid our movement from key to key.

Why not Bb, D or F? We need something that still retains a reminiscence of the original key. Coincidentally, these three pitches happen to outline the original key’s tonic chord. This isn’t always the case but it does work out quite well for us in this instance.

All of this being said, it is most important to follow your intuition. These are simply observations and analyses of music that I have found to be very effective and to more genuinely represent my emotions in the music.

This brings us to the passage framed by the second half of measure 9 to measure 15.

In these measures we can observe that the key of Eb major is established. You will notice the feel of this section is marginally more stable than the A major section that preceded it. This happens for two main reasons:

The key’s tonic (Eb) is exposed in both the highest and lowest registers.

The key’s leading tone and supertonic are both used and they both resolve in a rather traditional fashion.

These two characteristics alone wouldn’t necessarily create stability but in tandem with the sparse texture, and melodic figure of the middle line they create a kind of comfortable resting zone. This Eb major tonality isn’t without its own unique personality. If we can refer to a section as having an ‘unfettered’ tonal centre this might mean that there are no surrounding notes that would give the feeling of instability.

To make a huge generalisation we could say that all notes present fit into a key diatonically. We have to take this simplification with a bit of salt because the presence of these non-diatonic tones doesn’t automatically make a passage of music unstable. In this Eb major passage we will see a few notes or chords marked with *. This symbol is to indicate a contradictory tone. As mentioned earlier, contradictory tones are similar to the historically recognised non-harmonic tones. We won’t concern ourselves with how these contradictory tones resolve. Unlike non-harmonic tones which are meant to follow a logical set of rules towards resolution, the contradictory tone’s purpose is to distract from a potentially established key centre. There is no resolution. This could be similarly compared to improvising a solo and playing a ‘wrong’ note. The note is only really wrong if the performer wants it to sound wrong. If the performer repeats this ‘wrong’ note in close proximity to its first appearance the note suddenly loses that feeling of wrongness. This previous feeling of wrongness now starts to seem like rightness, contrarily this note now seems sacrosanct to the solo’s character.

We have to be a bit careful with how we consider these contradictory tones. A note that doesn’t fit the key signature doesn’t instantly qualify it as a contradictory tone. For example in ms. 13 and 14 in the middle voice there is a B natural which technically doesn’t fit into Eb major, but clearly in this line the B is just a leading tone to C. A similar argument could be made for the first of the * marked contradictory tones. They all move down by half step, they seem like simply a part of a chromatically moving line. So, how then do they qualify this as a contradictory tone? This is a somewhat subjective qualification, simply put the contradictory tone advertently hinders the diatonic construct of the music. For example the E natural in measure 10 bottom voice, goes directly against the other pitches surrounding it. It distinctly interrupts the feeling of a ‘pure’ Eb major. Similar conclusions could be said about measures 12 and 13’s contradictory tones.

Measure 14 and 15 show a slightly different usage of the contradictory tone. Here, we could interpret the A and C# as contradictory tones that prevent the low Bb from being too strong and obvious of a dominant (Bb7) chord in Eb major.

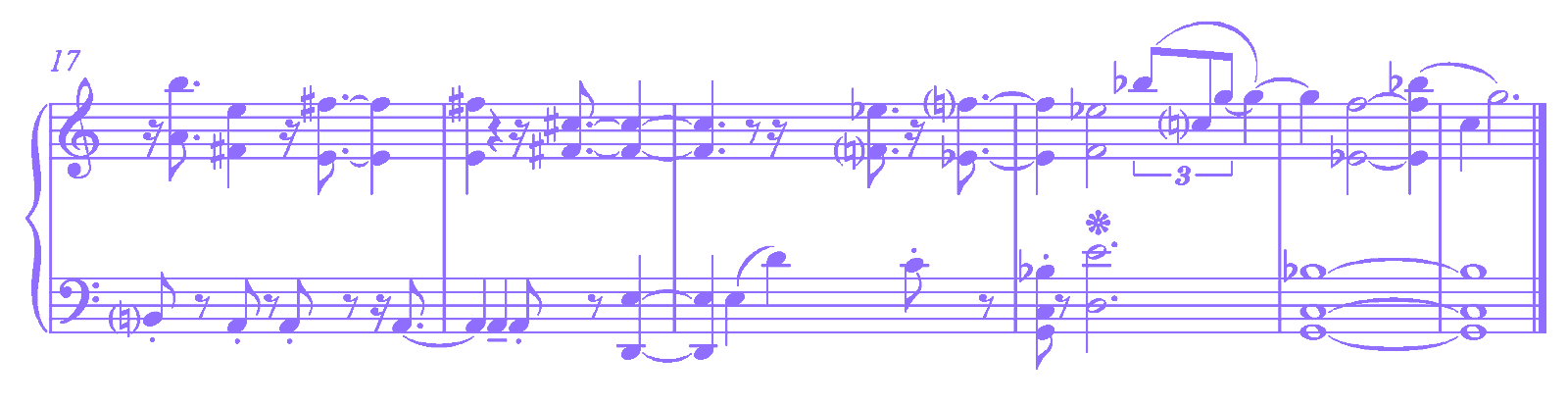

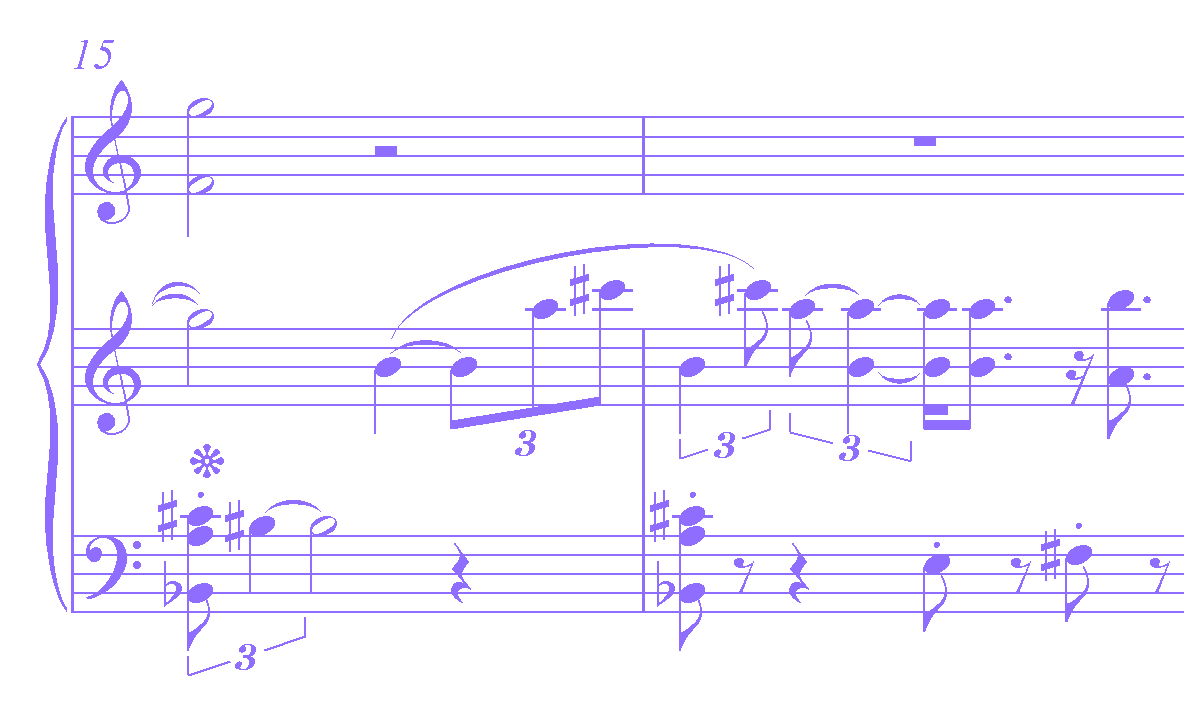

When we arrive in measure 15 and 16 we finally get our missing C# and B that were missing from our tone row in the earlier passage at measure 7-9. Whether we hear this as a resolution or a completion of the previous section is of secondary importance. Compositionally, what I wanted to do was get out of Eb major and work my way back to A major. To do this I employed a different method of transitioning to another key centre.

In measures 7 and 8 I made use of gradually introducing pitches of the new key, and gradually removing pitches from the old key. In measure 15 and 16 I made use of what could be equated to the direct modulation aka. static modulation of traditional music theory nomenclature. It works here because the lowest stave continues to play the altered dominant from Eb (our original key) while the middle stave is instantly in A major. There is no preparation to approach A major here but because it takes a while for the ear to adjust to this new tonality we don’t immediately recognise that we are in a new key.

Measure 17, 18 and the first half of 19 give us the most stable musical material yet. We have a totally pure A major uninterrupted for 10 full beats. How do we stay mobile? How do we avoid getting trapped in diatonicism? We follow our two previously established rules of avoiding a leading tone, and avoiding any dominant to tonic relationships. We also avoid any triads. By not having a G# or G natural here we kind of establish a non-confirmed tonal centre. In this case we can't say for sure what ‘A’ tonality we are actually in. It could fit A mixolydian, or A major. For that matter we could also hear this section as being based around F#, which would include F# minor and F# phrygian, lending further ambiguity to our tonal centre. Non-confirmed tonal centres allow us to stay nimble and are easier to get out of.